Postings on science, wine, and the mind, among other things.

Through the Self, Clearly

People represent their own mental states more distinctly than those of others: Thornton, Weaverdyck, Mildner & Tamir (2019) Nature Communications

Every one of us has a rich interior mental life. We have thoughts, feelings, moods, and sensations. Understanding these mental states is essential to our social lives. To make sense of why people act the way they do, or predict how others will act in the future, we must often look to their mental states. For example, if someone acted rudely towards you, you might consider their mental state and infer that they are tired and frustrated. Understanding the connection between this mental state and their action is useful because it allows you to plan your own future actions accordingly. For instance, you could avoid this person when you think they're short on sleep, or if you were feeling more charitable, you could devise a way to help them manage their frustration.

In my previous research, I have examined how the brain organizes its understanding of mental states [1], and uses that understanding to accurately [2], and automatically [3], predict people's future mental states. However, in these previous studies, I focused on the mental states of a "generic" other. That is, I carefully avoided telling participants precisely who they were making judgements about. Starting with the uncomplicated case of a generic other made these studies easier to design and analyze. However, it left us unable to examine differences in how we think about different people's minds.

In my most recent research, now published in Nature Communications, I sought to examine perhaps the most fundamental differences between minds: the difference between how each of us thinks about our own mind, versus the minds of other people. The self occupies a unique place in our mental landscape. Although each of us might seem like just another person from an outside perspective, we are each special to ourselves in numerous ways. For instance, we have privileged access to information about ourselves that no one else can ever truly experience. This includes both sensory information, like what our bodies feel like at any given moment, and cognitive information, which we gain through introspection (i.e., examining the contents of our thoughts). In addition to these qualitative differences, the self is also quantitatively unique, in terms of the sheer amount of experience we have with ourselves. No matter how much time one spends with a close friend or family member, it pales in comparison to the every waking moment one spends with oneself.

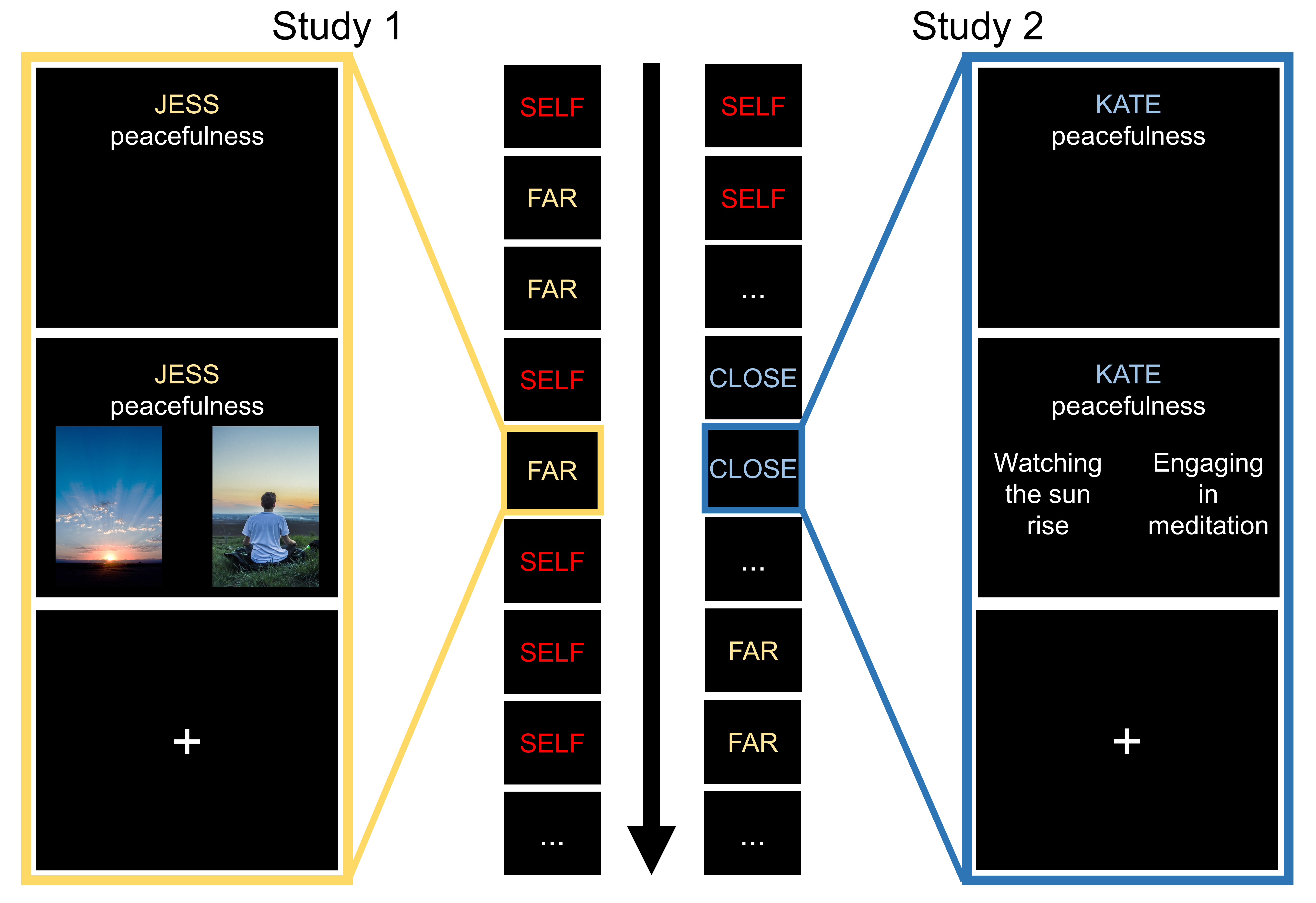

What consequences do these information asymmetries between self and other have for the way we think about mental states? We examined this question by asking participants in the fMRI scanner to make judgements about mental states - their own, and those of others - over the course of two similar experiments. Each experiment consisted of many trials - individual events - in which participants were presented with a pair of scenarios (either as text or pictures) and were asked to select which of the two scenarios would elicit more of a particular mental state in a specific person (see schematic illustration below). To ensure our results generalize broadly, we examined 30 different mental states in Study 1, and 25 in Study 2, each paired with dozens of different scenarios. The target people we examined were the self, a "close" target (e.g. a friend or family member nominated by the participant), and a socially distant other. The socially distant other consisted of an artificial biography tailored to be dissimilar, unlikeable, and comparatively unfamiliar to the participant, based on information that the participant had provided earlier.

We analyzed the results of the fMRI experiment by averaging across all of the trial in which participants thought about a specific target person experiencing a specific mental state. This produced 30 state-specific patterns of brain activity for each target person in Study 1 (self and far other) and 25 state-specific patterns for the target people in Study 2 (self, close other, and far other). We then calculated how similar each of the mental state patterns were to each other (within each target person) by correlating them together. Thinking about some states would thus generate more similar patterns of brain activity, while thinking about other states might elicit more different patterns.

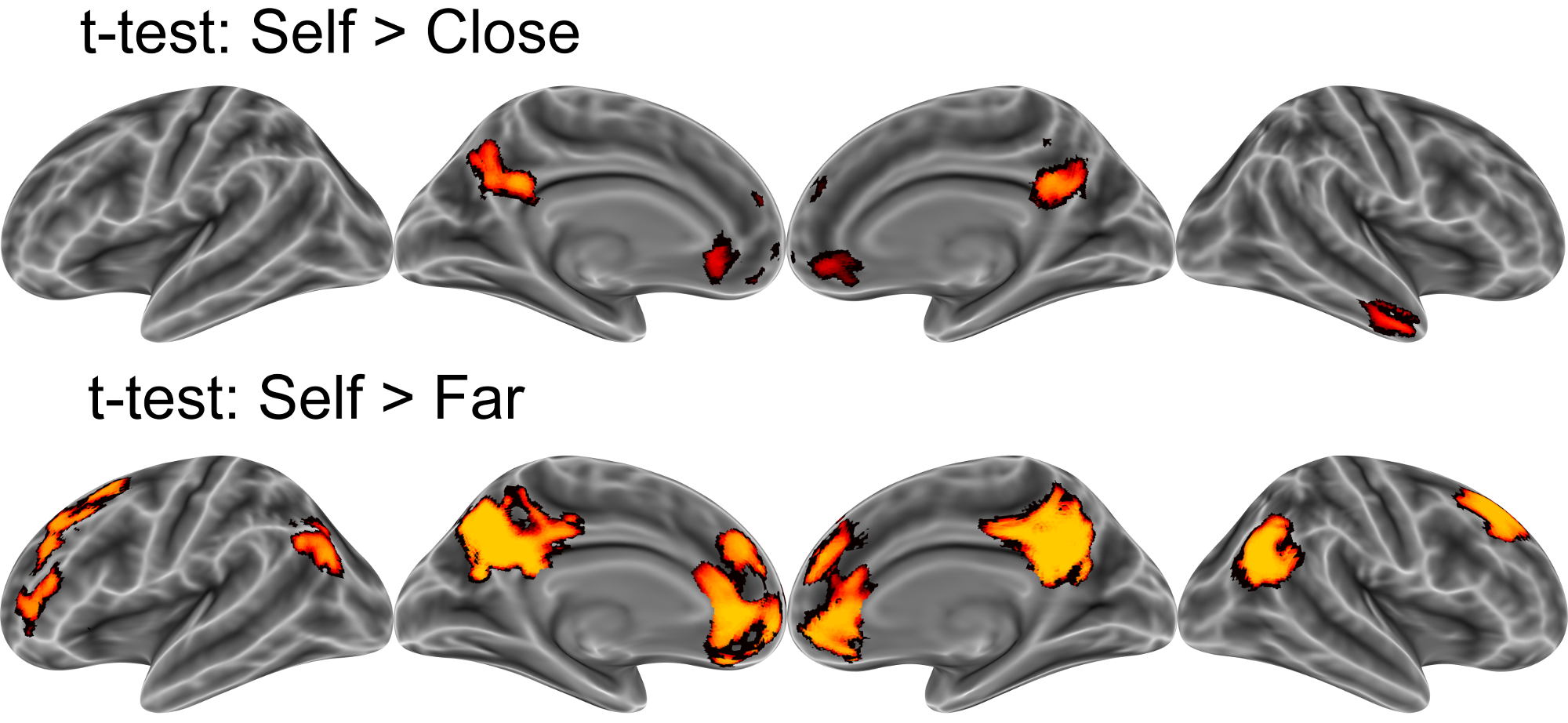

In previous studies [1] [2], we tried to identify the factors which shaped the similarity and differences between these mental state patterns. However, that wasn't our focus in this study. Instead, we were interested in the overall similarity between state-specific patterns within each target person. What we found consistently across studies is that thinking about other people's states elicits more similar patterns of brain activity than does thinking about one's own mental states. In other words, when you think about your own mental states, they are more clearly and distinctly different from each other than when you think about someone else's states. In Study 2, we observed this result throughout the brain regions in the figure below.

You can see this effect visualized in another way in the graph below. This figure plots the mental state patterns from Study 2 as a 2-D map, with each state from each target person occupying a specific location. The closer any two state patterns, the more similar they are to each other. The large dotted-line circles reflect the average distance between mental states within each target person. The large yellow dotted circle representing the self has a larger radius than the two dotted circles represent the close and far others. You can also see this reflected in the solid yellow circles which represent each mental state, and which are more widely scattered than the solid orange or red circles representing other people's mental states.

In addition to the fMRI data in Studies 1 and 2, we also collected complementary behavioral data in online experiments in Studies 3 and 4. In these studies, participants were presented with pairs of mental states, and asked to judge how similar those states would be for a particular person. For example, how similar are "self-pity" and "distrust" for your friend Jennifer? Participants made ratings on a six-point scale to reflect their judgements, and we analyzed the average similarity rating within each class of target person (self, close, and far in Study 3, close and far in Study 4). In Study 3 we found that people rated their own states as less similar to each other (i.e, more distinct) than the states of the far target person. In Study 4, we found that this effect extended, albeit weakly, to the difference between the close and far target, suggesting that some of the special nature of the self may be shared by the people close to us.

Altogether, these studies suggest that we think about our own mental states with greater clarity, granularity, or distinctiveness than we think about the states of other people, even close friends. This difference between self and other may contribute to many asymmetries in the way we reason about our own and others behaviors. For example, it may help explain why we tend to attribute fewer complex emotions to people unlike ourselves. The present findings may also help explain why our judgements of other people tend to be egocentric - that is, we tend to use our self-knowledge to understand others. Specifically, if our mental models of our own minds are considerably richer than our understanding of others' minds, then using ourselves as models for others may be quite a sensible strategy to adopt, at least when others are sufficiently similar to us. In future research, we hope to better understand the informational basis of the self-other difference in mental state representation. For instance, is this effect driven more by our privileged introspective access to our own minds, or by the sheer quantity of experience we have with ourselves?

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for more!

© 2019 Mark Allen Thornton. All rights reserved.